Make Love not War

Going Beyond Identity Politics While Thinking about the Vernaculars

Sailen Routray

|

| Copper plate recording a landgrant by Odia king Purusottama Deba in 1483 (Photo Credit - Wikimedia Commons) |

If you travel in the shared auto-rickshaws

that ply on the roads of the twin cities of Bhubaneswar-Cuttack and work as the

muscles of the cities’ transportation system, and you share the auto with a

young college-going couple, then often you’ll come across the following

phenomenon. Despite the fact that they speak Odia at home, often they would be

speaking in Hindi with each other. The fact these are Odia speakers of Hindi will

be evident from both the ungrammatical nature of the Hindi being spoken, and

its heavily accented texture. Hindi has definitely arrived in the campuses of

the Bhubaneswar-Cuttack metropolitan region, and how! Odia is definitely not

cool any longer.

But it might not be very productive to see

the relationship between the various languages in Orissa through an adversarial

prism. But that is what is often done, especially in the spheres of literary

and cultural production. For example, poets writing in ‘Indian’ languages such

as Kannada, Odia or Punjabi, often are dismissive of poetry written by Indians

in English. But many commentators have convincingly argued that this

adversarial relationship is of a comparatively recent origin.

For much of India’s cultural history, till

the advent of colonialism, a large number of people in most cultural regions

were pluri-lingual, spoke a number of languages, and used each one for a

specific set of purposes. Amongst litterateurs for example, Brajanatha

Badajena, a prolific Odia author who wrote the first recognizable piece of long

narrative prose fiction in Odia in the eighteenth century, also wrote in Hindi

and Sanskrit amongst other languages. Most Odia writers, throughout the documented

history of the literary use of the language, were at least bilingual, if not in

possession of the use of more than two languages.

It must be said that often the relationship

between languages in precolonial India, even if non-adversarial, was hierarchical.

As Sheldon Pollock has so brilliantly shown us, a large number of the modern

Indian vernaculars arose in the second millennium of the Christian Era out of a

process of contestation between what he terms as the Sanskrit Cosmopolis and

the emergent political formations that had their lives intertwined with the

vernaculars.

But the relationship between the

vernaculars and Sanskrit was not an adversarial one; they existed as a part of

the same cultural universe with Sanskrit often providing the templates of

cultural usage. There was perhaps never a fight between, for example, a

‘Sanskrit-ite’ and a ‘Bengali’. This was so for a very simple reason. These

language-based identities simply did not exist for a large number of speakers

of Indian languages.

|

| Letters and digits of Odia Script (Wikimedia Commons) |

It was perfectly possible for a Brahmin

hailing from the Midnapore area of north-Orissa/South Bengal in the early

modern period working in the court of the Nawabs of early eighteenth century

Murshidabad, to speak the north-Orissa dialect of Odia at home, do all his

(then, it was almost always a ‘he’) official work in Persian, converse with

neighbours in Bangla, write bhajans for

lord Jagannatha in the standard kataki Odia, and compose philosophical

treatises in Sanskrit without necessarily identifying oneself as ‘Odia’, Medinpuriaa’,

‘Bengali’ or ‘Persian’.

It is not necessarily that most identities

including linguistic identities were fluid/fuzzy in pre-colonial India, as

commentators such as Sudipta Kaviraj have argued. The fact of the matter was

perhaps far simpler. Language was simply not the basis of identity formation.

This meant that each language that a speaker had, was used for specific

purpose(s), and specific usage did not congeal into specific identities, as

Lisa Mitchell has shown for the Deccan in general and Telugu in particular. What

I want to argue here is a general normative point from which we’ll come back to

the specific case of Odia and Orissa. The position I want to state is this –

the very usage of language to further the aims of identity-based politics in

India has harmed them by uncoupling them from their ethical and creative

moorings.

Orissa was the first province/state to be

created on a linguistic basis in India in the year 1936. This took place after

a struggle of around fifty years for uniting all regions of British India that

had a majority of Odia speakers. Four jātis – Brahmins, Karana/Kāyasths, Khandāyats,

and self-proclaimed ‘Rajput’s, were primarily active in this movement for

unification (called desa misrana) of

Odia-speaking areas of British India. Brahmins, Karana/Kāyasths, Rajputs, and

to some extent Khandayats, still retain control over state-level politics in

the state. For around 38 of the last 40 years, Orissa has had a Karana chief

minister. This is curious since SCs and

STs (a large number of adivasi communities in Orissa have their own languages)

consist of nearly forty percent of Orissa’s population.

But while doing ethnographic research in Orissa’s

countryside, I have come across a still more curious phenomenon; in Odia-medium

government schools, Brahmin, Karana/Kāyasths, Khandāyats, and Rajputs seem

conspicuous by their absence. This observation needs to be corroborated by hard

data. But the broad pattern is unavoidable; the same jātis that were active in

the first third of the twentieth century in fashioning a language-based identity

(that eventually led to the creation of the first state created in India on a

linguistic basis in 1936) are now abandoning the language wholesale.

At the same time, the structures of power that

this language-based identity politics created seems to have entrenched the

privileges and positions of these four dominant jātis in Orissa. By creating a

type of politics where it is possible to have the identity of an ‘Odia’ without

being able to speak the language properly, language-based identity politics has

consolidated upper caste power in the state. Because of the unique dominance of

language-based identity politics in Orissa, and the exclusivist appropriation

of this politics by the upper castes, the stirrings of the subaltern social

groups that were vocal in articulating their concerns in cultural regions such

as the Tamil and the Maratha ones were subdued in Odia-speaking areas.

This has had a set of peculiar effects. Let

us give only one set of examples. Because of the fact that most skilled software

and telecommunications engineers seem to come from these four dominant jātis

(again, this is anecdotal and needs to be corroborated by hard data), and these

jātis have for all practical purposes abandoned Odia language for other

‘hipper’ languages such as Hindi and/or English, Odia is perhaps the only major

Indian language for which ‘Google’ search function is not available. Similarly,

most mobile phone companies available for sale in India did not have text-messaging

facilities in Odia for the longest time; this state of affairs has changed only

relatively recently. These are only two instances: the examples can be

multiplied.

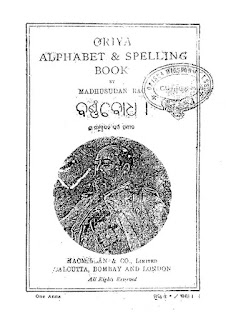

|

| Cover page of 'Barnabodha' 6th edition of an Odia primer printed in 1896 Author - Madhusudan Rao (1853-1912) Photo Credit - Wikimedia Commons |

Since the modernising upper-caste elite has

abandoned Odia, and has set itself up as an aspirational class for other social

groups, the language now finds it difficult to transition into the

‘post-modern’, ‘post-technological’ era. A conclusion is inescapable now; language-based

identity politics and concerns surrounding power have entrenched older forms of

jāti-centered political structures in Orissa. Now when the returns from such

politics seem to dry up, the four dominant jātis of karanas/Kāyasths, Brahmins,

Rajputs, and Khandāyats seems to have abandoned the language.

I want to argue that such a turn of events

is unavoidable. In the traditional Indian conception, language or speech (vāc)

is a devi, a goddess. If language is used for instrumental purposes, as most

identity-based politics does, such a process will create significant

distortions. This is not to argue that we abandon our vernaculars. I completely

disagree with dalit-bahujan scholars who seem to argue for embracing English

and abandoning the vernaculars.

The future of India lies in a plural

linguistic universe where the dominance of English and Hindi needs to be

contested. But language-based identity in Orissa does not seem to have produced

desirable results. Perhaps while speaking and talking about languages we need

to get back to the original sense of play and love that our vernaculars invoke.

We need to stop playing ‘politics’ with it. We need to make love with our languages, not

war.

Note: A Kannada version of this essay was published with the title ‘Odia

Matanaaduvudu Hemmeya Vishayavenalla (It is not a matter of pride to speak

Odia)’ in the year 2014, as a part of the Deepavali Special issue on Indian Languages of the Kannada newspaper Prajavani. The relevant page numbers are 276-278. Copyright rests with the author.

.jpg)

Language as always should simply be a means to express one's thoughts/ideas. India as a nation is recognised for its language diversity. This must remain intact. Scholars, researchers and linguists must emphasize on the love for languages and this must be imbibed at a very early age through modern education.

ReplyDeleteI would refrain from discussing language based politics. I only wish we as citizens of a great country like ours elect educated, broad minded leaders who would unite us further and not create divides amidst already existing ones.

May be it's time we stopped looking to electoral politics for the solution to all our ills and started doing things ourselves? To love languages and to act on this love, needs collective action for sure. But does that need to be subsumed under electoral politics?

DeleteInteresting articulation of the history of Odia's rise and fall as a language of interest along with sociological implications. Maybe its time to start a campaign called 'Make Odia Cool ( read contemporary)' By contemporary I don't mean kitsch or trite but a truly evolutionary approach that spans across cultural fields. Say for example typography . How about a week long typography festival across Bhubaneswar with artists playing forms and texts using different materials in large public spaces? Every space then becomes a meeting point for discussions, recitations, film screenings , theatrical performances aimed at capturing the modern Odia context in the shadow of a beautifully wrought typographical artwork.

ReplyDeleteA very great set of ideas. May be we should just start doing such things ourselves, without looking for any support and initiative from established organizations, be they governmental, non-governmental or corporate.

Deleteଆଗରୁ ପଢି ନ ଥିଲି, ଚମତ୍କାର

ReplyDeleteନମସ୍କାର, ସାର୍ । ପଢ଼ିବା ନିମନ୍ତେ ଏବଂ ମତାମତ ପାଇଁ ଧନ୍ୟବାଦ । ଆଶା କରେ ସବୁ କୁଶଳ । 🙏🏽

Delete